Tina Kryhlmann

Å håpe er å tilhøyre ei framtid. Ei kognitiv øving i å førestille seg endring, at noko skal skje som vil gjere tida som skal kome annleis enn tida som er. I gode tider kan håpet ta form av små, audmjuke ynskje om at noko skal inntreffe som løftar liva våre berre litt. Når verda kring oss er meir kaotisk, meir uoversiktleg og vond, lyt vi leite, finne håpet skjult i teikn og signal. Korleis kan ein navigere seg gjennom verdas rytmar og fenomen, finne fram til staden der eins eigen frekvens har plass, likeverdig i møte med andre sine?

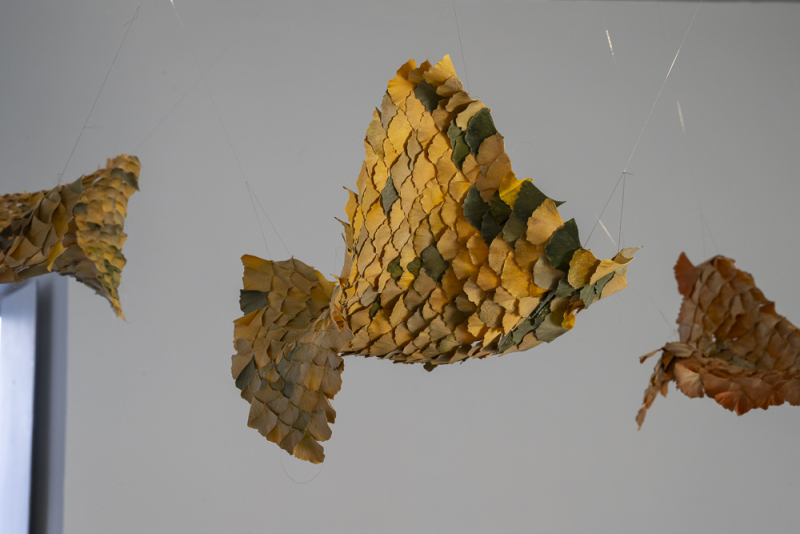

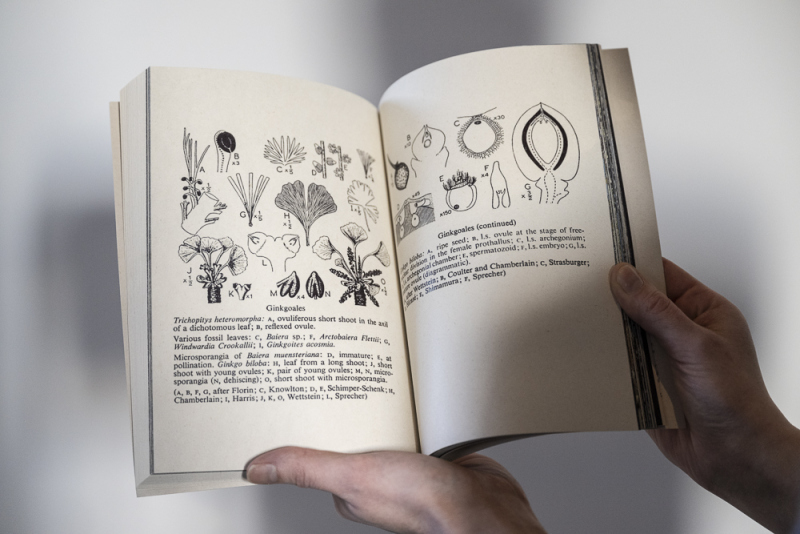

Av og til kjem håpet til oss i overraskande former der vi minst ventar å finne det. I etterkant av atombombinga i Hiroshima, vaks eit tre 1,1 kilometer frå episenteret. Treet heiter Ginkgo biloba, men er også kjend som Tempeltreet. I Japan kallar dei det “berar av håp”. Treet er med si storheitstid i Juraperioden for ein djupart og levande fossil å rekne, der det bind saman eit svimlande stykke fortid med notid. Det har vore relativt uforandra dei siste 100 millionar år, og er kjend for sin motstandsdugleik ovanfor forureining og sjukdom. Gjennom sitt arbeid med djuptid (historiske forlaup så lange at dei er uoverskodelege for individ) fekk Tina Kryhlmann vite om to tempeltre på prestegarden i Leikanger i Sogn, og la i 2022 ut på ei pilegrimsreise til fots frå Oslo. Der sov ho under trea, og plukka med seg blad som hadde falle til bakken medan ho var der – 26 i talet, som også var det antalet dagar turen hadde teke. Blada vart sydde saman med blad Kryhlmann har henta frå andre Tempeltre, der ho nyttar sitt eige hår som tråd. Saman vert blada eit romleg bylgjemønster, kjend som “seigaiha” (stille sjø), ein antikk representasjon av havet som symboliserer kraft og stille motstand. Grunna vifteforma på blada vert dette mønsteret danna når dei vert lagde kant i kant. Dei samansydde blada vert til store, svivande konstruksjonar som kan minne om teppe, eller kan hende eit lag av hud eller skjel. Ein stille motstand, ei beskyttande hinne. Blada er organiske og vil over tid endrast i fargar og tekstur. Til sist vil dei svinne bort, gå attende til jorda dei kom frå og såleis danne grobotn for nytt håp som kan spire og vekse der ein minst ventar det.

Tina Kryhlmann (f. 1986, Noreg) tok i 2017 mastergrad i Fri konst ved Konsthögskolan i Malmö. Ho har stilt ut ved mellom anna Galleri BOA, Høstutstillingen og KOHTA Kunsthalle i Helsinki. I 2023 var ho medarrangør og utstillar på Stedets tyranni i Brugata 15 i Oslo. I fleire samanhengar har Kryhlmann vore med på panelsamtalar med fokus på økologi, natur og kunst, eit ledd i hennar kunstnariske praksis, der ho gjennom ulike medium og tekst undersøker om og korleis ein økosentrisk praksis er mogleg.

Kunstnaren ynskjer å takke tempeltrea i Prestegårdshagen i Leikanger, Oslo og Bergen botaniske hager, Slottsgården, Universitetet i Oslo, Dronning Eufemias gate, Munch brygge, Youngs gate og i atriet på NMBU i Ås. Oda Marie Greve Mo m/ familie, Knut Henning Grepstad, Sverre Daae, Hoffgartnerar ved Det Kongelige Slott i Oslo, Botanisk hage i Oslo, tilsette ved NMBU i Ås. Allemannsretten, Steinar og Astrid, Sola kommune / Sagå på Rott, Researchgate, Erland Kiøsterud, Viktor Pedersen, Johanne Hestvold, Torgeir Nordbø, Gunnhild Torgersen, Andrea Bakketun, Fivel Kryhlmann og Hanna Sjöstrand.

Utstillinga er støtta av Norsk Kulturfond v/ Kulturrådet, Billedkunstnernes Vederlagsfond, regionale prosjektmidler frå Kunstsentrene i Norge og Norske Kunsthåndverkere.

Les Justine Nguyens anmelding av utstillinga i Morgenbladet her.

Foto: Thor Brødreskift

To hope is to belong to a future. A cognitive exercise in imagining change; something will happen that will make the time to come different from the present. In good times, hope can take the form of small, humble wishes for something to occur that lifts our lives just a little. When the world around us is more chaotic, more incomprehensible, and painful, we listen, finding hope hidden in signs and signals. How can we navigate through the world's rhythms and phenomena, finding the place where our own frequency has room and is equal in encounters with others' frequencies?

Sometimes hope comes to us in surprising forms, where we least expect to find it. In the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, a tree survived 1.1 kilometers from the epicenter. The tree species is Ginkgo biloba, also known as the maidenhair tree. In Japan they call it the "bearer of hope." Connecting a dizzying stretch of the past with the present, with its heyday in the Jurassic period, the tree is a deeply-rooted living fossil to be reckoned with. It has been relatively unchanged for the last 100 million years and is known for its resilience to pollution and disease. Through her work with deep time (historical processes so long that they are incomprehensible to an individual), Tina Kryhlmann learned of two maidenhair trees at the rectory in Leikanger, Sogn, and, in 2022, set out on a pilgrimage on foot from Oslo. There she slept under the trees, gathering leaves that had fallen to the ground while she was there – 26 in number, also the number of days the trip had taken. Using her own hair as thread, the leaves were sewn together with leaves Kryhlmann had collected from other maidenhair trees. Together, the leaves form a spatial wave pattern known as seigaiha (still sea), an ancient representation of the sea that symbolises power and quiet resistance. The shallow fan shape of the leaves is formed when they are placed edge to edge. The sewn leaves become large, floating structures that can resemble a blanket, or even a layer of skin or scales—a quiet resistance, a protective membrane. The leaves are organic and will change in color and texture over time. Eventually, they will fade away, return to the soil they came from, and thus form fertile ground for new hope that can sprout and grow where one least expects it.

Tina Kryhlmann (b. 1986, Norway) received her master's degree in Fine Arts from the Malmö Academy of Fine Arts in 2017. She has exhibited at Galleri BOA, Høstutstillingen, and KOHTA Kunsthalle in Helsinki, among others. In 2023, she was a co-organizer and exhibitor at Stedets tyranni at Brugata 15 in Oslo. She has participated in panel discussion focussing on ecology, nature, and art in a variety of contexts. Through various mediums and texts, Kryhlmann’s work examines whether, and how, an ecocentric practice is possible.

The artist would like to thank: the maidenhair trees in Prestegårdshagen in Leikanger, Oslo and Bergen botanical gardens, Slottsgården (University of Oslo), Dronning Eufemias gate, Munch brygge, Youngs gate, and in the atrium at NMBU in Ås; Oda Marie Greve Mo and family, Knut Henning Grepstad, Sverre Daae, Court gardeners at the Royal Palace in Oslo, Botanical garden in Oslo, employees at NMBU in Ås; Allemannsretten, Steinar and Astrid, Sola municipality / Sagå på Rott, Researchgate, Erland Kiøsterud, Viktor Pedersen, Johanne Hestvold, Torgeir Nordbø, Gunnhild Torgersen, Andrea Bakketun, Fivel Kryhlmann, and Hanna Sjöstrand.

The exhibition is supported by the Arts and Culture Norway, the Norwegian Cultural Foundation, the Norwegian Visual Artists Fund, regional project funds from the Arts Centres in Norway and the Norwegian Association for Arts and Crafts.

Read Justine Nguyens review of the exhibition for Morgenbladet here. (In Norwegian)

Photo: Thor Brødreskift